Habitat / Amsterdam (2021) 1h45min

Habitat: The Seismic Ritual of Nakedness and Spiritual Awakening

The Body as a Sacred Territory

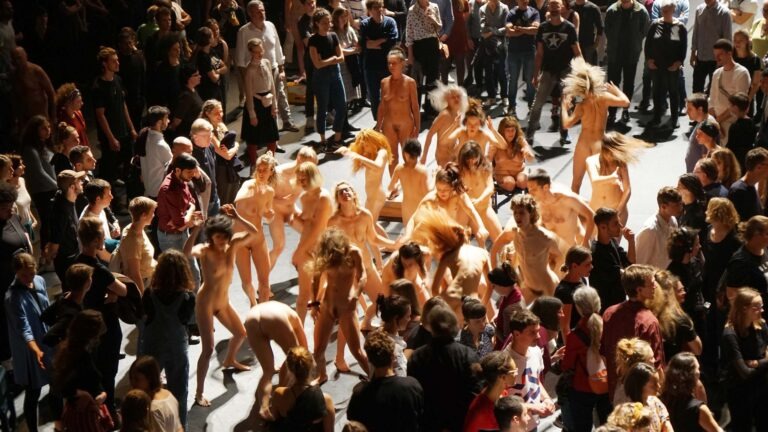

In *Habitat*, it reimagines the human body as a site of liberation. The performance, staged in Amsterdam in 2021, unfolds as a 105-minute exploration of shared vulnerability. Through the fearless use of nakedness, Uhlich transforms what society deems private into a spiritual public act. This openness fosters a collective encounter, inviting all who witness to reconsider the sanctity of flesh.

10 & 11 November 2021 / 21:00

Frascati

Nes 63

1012 KD Amsterdam

Netherlands

Concept, Choreography Doris Uhlich

Dancers:

Philemon Mukarno ,Merel Steenbrink, Anna Siller, Avantika Tibrewal, Azad Jamshidnezhad, Bella Bouman, Cees Chaudron, Chris van Berge Henegouwen, Ella Max Jonker, Ingeborg de Lange, Inger Marin van den Berg, JongSung Myung, Klaus Lengefeld, Luise Kostopoulos, Maria Tepper, Mim Schneider, Olga Tamara Briks, Rolf Steenwinkel, Rolf van der Tang, Saeed Asadsangabi, Sarah Hanses, Stefan de Groot, Ute Frederich, Clément Charier, Dine Mentel, Jiayun Zhnag, Sissi Grasser, Hannah Sampe, Vera Rosner-Nógel, Akari Takimoto, Anne Chris van Doesburg.

Nakedness as Liberation

Nudity in *Habitat* is never erotic; instead, it is a radical act of emancipation. By stripping away fabric, performers also shed layers of social constraint. Every tremor, ripple, and wobble becomes a declaration of worth. Uhlich calls this her “fat dance technique” — movements that allow bodies of all sizes, genders, and conditions to vibrate with unapologetic power. In doing so, she transforms bodily imperfection into divine rebellion.

The Spiritual Pulse of Flesh

At the core of *Habitat* lies a paradoxical spirituality — a wordless prayer made through motion. The dancers, glowing under stark light and driven by pulsating techno rhythms, enter a trance of unity. The music’s seismic vibrations bind mind and body, flesh and frequency. In this merging, nakedness becomes a form of transcendence. The body ceases to be an object and transforms into a vessel of shared consciousness.

The Pandemic Paradox: Distance and Desire

When the Amsterdam version took form under pandemic regulations, physical intimacy became forbidden. Masks replaced closeness; distance replaced touch. Yet, within this limitation, a deeper spiritual hunger emerged. The performers’ isolation became a meditation on longing itself. Stripped of proximity but not intent, they danced the ache of the human condition — the desperate need for others, even in separation.

Flesh, Shame, and the Gaze

Spectators of *Habitat* rarely remain comfortable.

The stage dissolves into open space, forcing a confrontation between clothed observer and naked performer. Some viewers blush, others recoil, but all must face their own conditioning. The work exposes how shame lives not in the body, but in the gaze cast upon it. Nakedness here is not spectacle but mirror — the audience’s reflection, raw and unresolved.

From Vulnerability to Communion

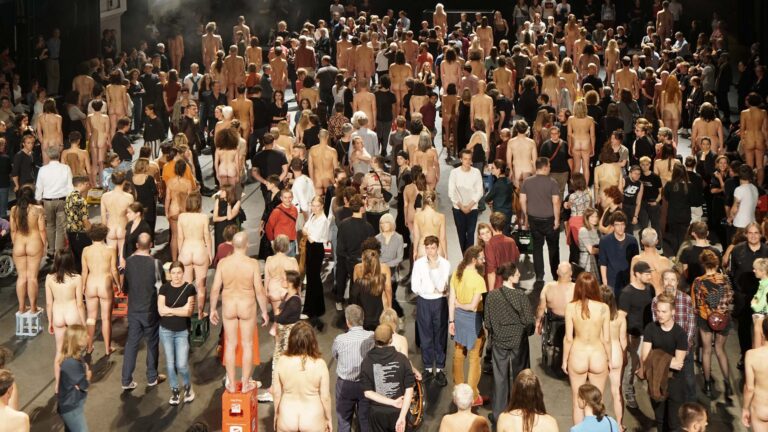

The beauty of *Habitat* lies in its democratic spirit. Uhlich assembles ensembles of diverse bodies — aged, disabled, corpulent, trans — celebrating life in all its unvarnished forms. These performers do not aim to entertain; they strive to unite. Their sweat and movement turn the space into a living ecosystem, dissolving boundaries between self and other. The result is not performance — it is communion.

Sound as Spiritual Catalyst

The relentless techno pulse by DJ Boris Kopeinig serves as both heartbeat and ritual drum. It drives the bodies into collective vibration, awakening primal energy from within. The sound becomes a tool of transcendence, guiding dancers toward states of awareness unreachable through stillness. Each beat echoes a silent truth — spirituality can be kinetic, ecstatic, and defiantly physical.

The Enduring Echo of Corporeal Truth

*Habitat*’s resonance lies in its honesty. Its message is both ancient and urgent: spirituality begins in flesh. Even stripped bare, during times of fear and isolation, the body remains our most sacred vessel. Uhlich’s work invites us to inhabit our skin more deeply, to listen to the rhythm that connects us all. In a culture obsessed with perfection, *Habitat* offers something far more dangerous — and divine — authenticity.

“Furthermore, everyone is completely undressed, young and old, male or female, of all ages and nationalities. Even a woman in a wheelchair with paralyzed legs is part of Habitat/Amsterdam by the Austrian choreographer Doris Uhlich. The bodies vibrate, tremble, dance, sway, legs are spread, it is a contemporary Garden of Earthly Delights by Jheronimus Bosch. According to Uhlich, her choreography is a ‘praise of the naked body’ and the theater where it takes place is a ‘utopian place’.

It is clever of the performers that their nudity is no hindrance to making any dance movement. As a spectator, you are forced to ask questions. Is this a provocation or rather a tribute to the naked body? Is this eroticism? The vibrating movements of women kneeling on the floor border on pornography, but it is not. We, the spectators, experience shame in looking at all that nakedness, writhing and sweating right at your feet.”

“The audience walks between the dancers, and suddenly one of them lies down next to you or pushes his or her body, moving fiercely back and forth, against one of the pillars of Frascati 1. Wet spots from sweat remain on the ground. The disabled woman who crawls in and out of her wheelchair, with powerless legs, makes you shiver, but is that all justified? Beauty ideals of slim and young, with which the advertising world beats us numb, Uhlich sweeps off the table in one go: some dancers are deep in their sixties or seventies, with a body marked by age.

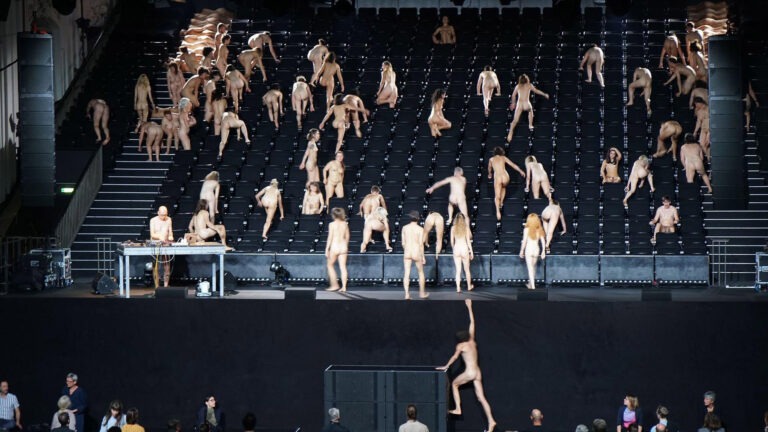

The group choreography is propelled by electronic sounds from the also naked DJ Boris Kopeinig. Techno beats transform the room into a naked disco. The dramatic build-up is remarkable, and with that Habitat/Amsterdam transcends simple provocation. First, the performers move freely through the space, sometimes the heat of that one body just hits your face, so close it often is. Then they move to the galleries of Frascati and suddenly they take their seats on the chairs of the stands: there sits, as it were, a naked audience watching the visitors on the playing floor.

The music moves in waves from extremely loud and rhythmic to still. The ‘habitat’ from the title, which literally means ‘living environment’, is the sanctuary for unashamed nudity. Uhlich presented the performance in Vienna in collaboration with Tanzquartier Wien. There she also made a Covid-19 version with naked bodies covered by plastic. It was her direct response to the consequences of the corona crisis, in which there is a great taboo on physical intimacy and proximity to others. Face masks and distance even made us fear for others.

In each city Uhlich works with new performers, as well as in Amsterdam, hence the title Habitat/Amsterdam. Attending a performance full of intimacy like this is also a new experience for the audience. The traditional distance between the hall and the stage has been lifted, sometimes the naked dancers look you straight in the eye and break through your comfort zone with their proximity. Towards the end, the techno beat increases in tempo, the performers throw their arms up high and the entire playing floor seems like an ecstatic dance of freedom, a frenzy of waving arms and dancing bodies.

It is striking that there is actually no bond between the audience dressed against the cold and the performers with their vulnerable skin. Nobody danced along, nobody sought any form of approach despite often inviting performers. Is it still something of shame and unfamiliarity that prevents the spectator from doing so? Because that is the paradox that makes you think: so much intimacy right around you and at the same time the spectator himself creates so much distance.”

Essay: Rehearsing Realities (Together)

…and as we gathered at the entrance of Frascati 1 – each of us bent over our phones, carefully watching and listening to the news – we entered a new lockdown together. This time, the theater remained open. As a last resort to come together. That is, at least for now.

“HABITAT”: PERFORMING A LANDSCAPE OF NAKED BODIES

In Ways of Seeing (1972), John Berger stated that “the way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe.” In other words, our perception is influenced by beliefs and convictions often instilled from external sources, without their truthfulness and reliability being unquestionable.

Not by chance, the viewer’s gaze is the main focus of performance art, which for over 60 years has continued to challenge it, attempting to bend, tear, and crumple it just as one would do with a piece of paper. Doris Uhlich, an Austrian choreographer and performer, knows this all too well. Since 2006, she has employed naked bodies or bodies with physical disabilities as a counterpoint to common thinking, social beliefs, and mental patterns in her choreographies. Uhlich’s aesthetic explorations find their roots in a direction that began in the 1960s, alongside artists such as Carolee Schneeman, The Living Theatre, The Performance Groupe, the Viennese Actionism, Butoh (the Japanese dance-theatre), Hannah Wilke, and Fernando Arrabal, to name a few. Though each of them pursued unique and personal endeavors, they all shared the use of the naked body as a symbol of primordial human innocence—a state of being that transcends all differences between individuals in a democratic manner devoid of any erotic connotations.

However, even though nudity used as an aesthetic material alludes to the liberation of the body from oppressive cultural communication codes, it is not exempt from misinterpretations, conflicting reactions, and the potential to cause discomfort among observers. I had this confirmed as a spectator during a recent performance by Uhlich at Metropolis, an international festival of site-specific art and performance held in unconventional locations in Copenhagen. Despite believing I was immune to embarrassment, I cannot deny feeling unease while witnessing 40 naked bodies moving naturally in space. The performance in question is Habitat, a project on which the artist has been working since 2017 and has been realized in various countries, including France, Austria, and Germany, involving both professional and non-professional local performers/dancers in creating choreographies of movements. The context of this latest version is Refshaleøen, a former industrial site located in the harbor of the Danish capital, which was initially a separate island but is now connected to the larger island of Amager.

The initial segment of this itinerant collective performance unfolds within container storage. We are the last group to arrive, and the rest of the audience is already there, numerous, with the 40 participants lying on the ground, one atop another. I’m not the only one experiencing a blend of embarrassment and unease. The atmosphere feels rather tense. Something is about to happen. Some performers start to move and navigate through the space, while others approach the audience without establishing direct contact. Their movements are not conventional dance steps but essential gestures that stimulate the body, leaving it vibrating. A simple gesture, yet remarkably effective in imposing the body’s corporeality on the observer’s gaze. The slow tempo intensifies, and, like in a modern ritual, the rhythm becomes more urgent: some of them leap onto the containers, pounding on them and creating a cloud of dust that makes the sharp and thunderous noise visible. At the performance’s climax, the 40 participants exit, and we follow them like in a religious procession.

In another segment, an abandoned and rusty fishing boat, those bodies reveal themselves as carriers of diverse identities, each evoking a particular empathy. These nude bodies belong to 40 individuals of different ages and genders: some young, others much older. It was probably not difficult for some to take part, while participating in this performance might have been a rite of exorcism for others. The scars of a mastectomy on a woman’s body lead me to deduce this. It is inevitable to linger on their figures, trying to reconstruct their stories and personalities because, in the end, their presence is also a source of curiosity. Everyone likely wonders where they found the courage to make themselves vulnerable before our eyes.

Gradually, the 40 individuals become a unified body. It’s not the rhythmic synchronization of movements that unites them, but the act of swaying together, holding hands, giving the impression of floating and vibrating as if they were one large organism. This impression is amplified by the techno tracks of Boris Kopeinig, which accompany and extend the energy of this singular movement. Personally, it was one of the most captivating moments of this performance.

Habitat is a complex performance in its execution. Uhlich had to deal with precarious structures – being in a former industrial area – with vast spaces and the need to coordinate the movements of both performers and the audience from one point to another. A drawback of the performance was the time to move between the various locations, which sometimes was a distraction, diminishing the intensity and energy attained in the five parts. On the other hand, these vast spaces have also revealed the strength of this Danish production. Uhlich didn’t merely choreograph the movements of the 40 performers but succeeded in integrating them into the space, blending the environment with the group of 40 naked bodies, now transformed into a unified, sprawling organism, blurring the boundary between them.

Indeed, this intermediate space and connection between the human and non-human exude poetry. At that moment, the gaze expands, overlooking the specifics of those naked individuals and the windswept landscape of Lynetteholmen, the farthest tongue of land in Copenhagen that hosted the final stage of Habitat. Uhlich demonstrated her choreographic prowess, crafting a performance that radiated beauty, skillfully orchestrating the elements at her disposal. The naked body, liberated from societal constraints, shed its erotic connotations and returned to its human essence. As a result, it reclaimed its place as a natural entity within an interconnected ecosystem of relationships and dialogue.

Habitat is a political performance, but not in the conventional sense. It does not align with any partisan ideology; instead, it operates on the gaze, hinting at the potential emancipation from the common thinking imposed by established social norms. It invites us to seek novel expressions of beauty and humanity because, in Berger’s words, “we never look at just one thing: we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.”